Global counter-terrorism is fundamentally changing, as is evident in recent patterns of terrorist designation. For decades, the US Foreign Terrorist Organisation (FTO) list has been a bellwether of counter-terrorism policies – countries around the world, both US allies and others, have often followed the list when updating their own terrorist lists. However, a strong divergence is becoming apparent.

The United States under President Donald Trump is shifting course by focusing counter-terrorism resources on groups traditionally thought of as criminal organisations – drug traffickers in Mexico and gangs in Haiti, for example. The United States has added 12 such groups to its FTO list this year so far. Most other countries, however, have not added these criminal organisations, or any criminal groups, to their own terrorist lists. Traditional US partners like European countries do not seem to view crime groups as appropriate subjects of counter-terrorism. For the first time ever, most other countries are not following the FTO list.

Meanwhile, US allies increasingly focus counter-terrorism on far-right organisations. Canada and the United Kingdom each include eight far-right or white supremacist organisations on their terrorist lists, and the EU, Australia, and New Zealand list such groups as well. The US FTO list, however, does not include any far-right organisations.

This article analyses global patterns in terrorist designation. It describes the wave of criminal groups added to the FTO list this year, explaining why this occurred and why it is so unusual. The article then discusses the recent pattern of other countries listing far-right organisations. It concludes with broader trends and implications.

Terrorist designation: widespread and consequential

One of the most widespread and enduring legacies of post-9/11 counter-terrorism is terrorist designation – the labelling of certain entities as terrorist organisations, which usually imposes serious punishments on the groups and those who might support them. Some aspects of the “war on terror,” like major military interventions and drone strikes, have waxed and waned over time, but terrorist lists seem to only grow.

Dozens of countries, along with international institutions like the United Nations and the European Union, now maintain terrorist lists. This is not only a Western phenomenon. Russia and China, India and Pakistan, Argentina, and Nigeria all have their own terrorist lists, as does the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. Hundreds of armed groups around the world appear on at least one national or regional terrorist list.

The terrorist lists are highly diverse. This is due to different definitions of terrorism, legal restrictions, and distinct goals regarding terrorist listing (e.g., foreign policy vs. domestic policy). For example, the US FTO list, with 81 organisations, includes only non-US groups, and about half are Islamist organisations. The UK lists a similar number of groups (84), but a clear majority (about 70 percent) are Islamist, and the list includes US-based and domestic UK organisations. The European Union list contains 22 organisations, from Europe and abroad, and only about one third are Islamist. Countries in other regions, with distinct threats and different types of legal systems (e.g., Russia and China), have terrorist lists that are even more dissimilar.

Research shows that terrorist designation can lead to important consequences. In the United States, terrorist designation has led to tens of millions of dollars frozen or seized from listed organisations. Some studies show that the financial pressure on designated terrorist groups is associated with subsequent reductions in terrorism, at least for certain kinds of groups. Terrorist designation also has implications for civil war, sometimes hindering peace processes. There are also substantial human rights implications, including when groups and individuals feel they have been wrongly listed. In spite of these costs, terrorist designation as a practice is increasingly common, with organisations often added to lists, and few organisations removed. Terrorist designation can provide a helpful signal to the international community about priorities, and within each country, it can help counter-terrorism agencies coordinate and prioritise on certain terrorist threats.

The US FTO list as the most influential CT signal

One of the oldest terrorist lists is the US FTO list, launched in 1997 and maintained by the State Department Bureau of Counterterrorism. The list initially included 28 FTOs, such as Hamas, the PKK, and the Shining Path. For groups to be included, they needed to meet three criteria: they should be foreign, engage in terrorist activity, and threaten the security of US nationals or US national security. Once an organisation is designated, it becomes a crime to provide “material support” to it; non-citizens can be barred from the United States if they are deemed to be associated with the group, and US financial institutions should freeze any funds associated with the organisation. Over the years, dozens more groups have been added, often groups linked to al-Qaeida or the Islamic State. The United States has other terrorist lists, like Specially Designated Global Terrorists (SDGTs), but these lists are often more specific and do not include the “material support” restriction. FTO status also seems to be unique for its notoriety, its international visibility.

Since the FTO list was first created, and certainly since 9/11, it has been a beacon of counter-terrorism trends, a clear indicator of groups seen as global counter-terrorism threats. Several analyses of countries’ and international institutions’ terrorist lists have shown that the FTO list is the most globally influential country terrorist list. One of the strongest indicators of whether a country will put a group on its own terrorist list is if the group had previously been labelled as a US FTO. This is the case for Western allies of the United States, but also for countries like Russia and Pakistan, as my own research has found. One study calls the United States the key global “trendsetter” in terrorist designation. Perhaps the most comprehensive analysis of designation, studying all terrorist lists in the world, concludes that “the United States is the most important leader in terrorist designation and many other countries’ lists follow the FTO list.” That article was published in 2023 – times have changed.

War on crime: The FTO list gets a major makeover…

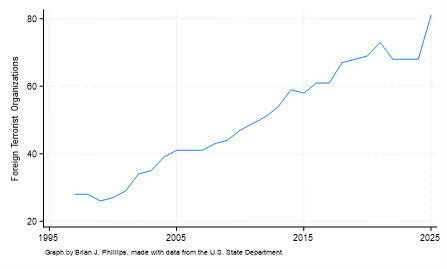

President Trump’s second term, starting in January 2025, has altered many aspects of US foreign policy, and counter-terrorism is no exception. Since February, the State Department has added 14 groups to the FTO list. This is the biggest expansion of the list since its creation. The graph below shows that the number of FTOs has steadily increased since 1997, but the biggest jump, the steepest spike, occurs in 2025 with the 14 new groups. (The bump a few years earlier is the result of the first Trump administration listing seven new groups, and the subsequent Biden administration later removing several different organisations.)

Groups on the US Foreign Terrorist Organisation list per year, 1997-2025

Even more noteworthy than the quantitative increase is that twelve of the new groups are qualitatively different from other FTOs – they are Latin American criminal groups. The FTO list now includes the Sinaloa Cartel and five other Mexican drug cartels, and gangs from Ecuador, El Salvador, Haiti, and Venezuela. This is a major change in policy, and it is an unusual understanding of “terrorist organisation.”

Declaring criminal groups to be terrorists is a fundamental change because for decades, experts have used separate frameworks – theories, laws, etc. – for criminals and terrorists. Criminals are motivated primarily by profits, while terrorists are ultimately driven by political goals like regime change or policy concessions. A classic analysis of more than 100 definitions of terrorism found that most definitions identify terrorism as having a “political” element, such as an ideological or religious motivation.

The differences between criminals and terrorists are not only theoretical. Distinct types of violence have unique causes and therefore solutions. Unemployment can encourage criminal violence, but it is often unrelated to political violence like terrorism. In another example, killing or arresting group leaders often reduces the violence of terrorist or insurgent organisations, because charismatic leadership and appearances can be important for mobilisation. But leadership removal frequently causes more violence when criminal groups are targeted, as competition for high-stakes drug territory upends business relationships. There are connections between criminals and terrorists, and it has long been noted that some criminals use terrorist tactics, but these two group types are generally considered distinct for good reason.

The new criminal groups on the FTO list might arguably meet the three criteria for designation – being foreign, using terrorism, and threatening US security or US nationals. However, the motivations behind (and thus solutions for) cartel violence suggest it is probably not what most people think of as “terrorism.” In terms of these groups directly threatening US national security, this is also debatable. Some of the twelve criminal FTOs have harmed US nationals, but so have many insurgent and criminal groups around the world, and most such groups are not on the FTO list.

The invention of a new criminal type of FTO is consistent with Trump’s militarised approach to crime, and his more general use of national security or “emergency” justifications for unprecedented actions. Trump had proposed designating Mexican cartels as FTOs as early as 2019, in his first term, although he eventually backed off the idea because Mexico and others opposed the move. In the meantime, he sent the military to the Mexican border. More recently, he ordered the US military to start using force against foreign drug cartels, including killing eleven people in a missile strike near Venezuela. In another unprecedented move, he has sent the National Guard to the streets of Washington, D.C., to deter ordinary crime. These actions could be seen as part of a pattern of extreme domestic politics signalling, showing voters that the government is “doing something,” regardless of consequences. Some of these policies also facilitate advances on a related issue that is a priority for the president, reducing immigration from Latin America.

… but other countries aren’t following this time

The new US focus on counter-terrorism is not yet catching on. Most US allies have not added any criminal organisations to their terrorist lists, in spite of some activity from the new US FTOs in Europe and Australia. Furthermore, the vast majority of countries and international institutions have refrained from labelling their own local criminal organisations – such as British gangs or the Italian Ndrangheta – as terrorist organisations.

There are some exceptions. Canada added some of the Latin American criminal groups to its own list at the same time as the US FTO designation. However, sanctions experts argue that Canada updated its terrorist list under pressure – it was a “direct response” to threatened US tariffs. The United States apparently tried to get other countries in Latin America to follow its counter-terrorism approach. A few states with Trump-friendly leaders, like the Dominican Republic, have declared one Venezuelan cartel to be a terrorist organisation. Others in the region, such as Brazil, have declined such pressure. One other notable case of a country using an explicit counter-terrorism framework against organised crime is El Salvador – but the authoritarian Salvadoran government has done this for years. Overall, the lack of corresponding changes to other countries’ terrorist lists suggests a profound change in global counter-terrorism: few countries are updating their terrorist lists to follow the new wave of FTO designations.

Why aren’t other countries following? It could be in part due to general opposition to the Trump regime, at least for some countries. However, it is more likely that most countries do not see criminal organisations as an actual threat on par with traditional terrorist organisations such as al-Qaeida and the Islamic State. Additionally, they probably view counter-terrorism approaches like military raids or deradicalisation programs as excessive and counterproductive (in the case of raids) or unlikely to affect non-ideological groups (in the case of deradicalisation). In short, they do not see criminal groups as terrorists.

Outside the US, a growing focus on far-right terrorism

Another reason countries might not be focused on criminal organisations is that other types of violent non-state actors are seen as more of a priority – like the far-right. The decline in Islamist terrorism since the 2015 peak of Islamic State-related activity, combined with a growing melange of generally far-right extremism, has Western governments shifting counter-terrorism resources toward the far right. The 2019 Christchurch, New Zealand, attack – where a white supremacist killed 51 people at a mosque and Islamic centre – seems to have been a turning point. Beyond the death toll, the attack stood out for being livestreamed to a large audience and producing a manifesto that has inspired subsequent attacks and attempted attacks worldwide.

The increasingly visible movement also led to a terrorist designation. The United Kingdom first proscribed the British group National Action in 2016. It has added seven other far-right groups, both local and from other countries, since 2020. Canada proscribed two far-right groups in 2019 (UK-founded Blood and Honour and its armed wing, Combat 18), and others in 2021. Australia, New Zealand, and the European Union added far-right groups to their terrorist lists in recent years as well, such as the white supremacist US groups The Base and Atomwaffen, and UK-based Sonnenkrieg Division. The banned groups and their various branches have been associated with a substantial amount of violence, such as the killing of a German politician, fatal shootings at an LGBTQ bar, and attempted lethal attacks disrupted by police.

The United States has mostly refrained from adding such groups to its terrorist lists. The influential FTO list, with its 81 organisations (including twelve criminal groups), has not been updated to add the far-right or white supremacist groups listed by partner countries. A few far-right groups or individuals have been added to other US terrorist lists. The Specially Designated Global Terrorists list includes several far-right groups: the Russian Imperial Movement, the Nordic Resistance Movement, and the Terrorgram Collective. However, as noted above, these listings are not as visible or as impactful as the FTO designation. As one expert has argued, the United States has been “reluctant” to designate far-right organisations, more so than its longtime allies.

It should be acknowledged that part of the reason for differences between the FTO lists and those of other countries is that the FTO list, as its name implies, only includes foreign groups. It legally cannot include US-based groups like The Base or Atomwaffen. But this does not explain why foreign groups such as the Nordic Resistance Movement or Combat 18 remain off the FTO list.

Part of a broader pattern

Of course, terrorist designation is not the only sign of disagreement between the United States and other countries on security issues. The United States is separating from its traditional allies on issues like the importance of NATO, relationships with major tech companies, and the threat of climate change, to name a few. The rift over counter-terrorism priorities is surprising, however, because the US-led coalition (with some clear dissent, like the 2003 Iraq war) had defined counter-terrorism priorities for many countries since 9/11, and to a broader degree in the entire post-Cold War era. The apparent falling-out is occurring on numerous issues, but the contrasting new additions to terrorist lists underscore the significant change in priorities.

The future of terrorist designation?

The recent divergence in terrorist listing between the United States and its partners raises questions about the purpose and future of terrorist designation. Is a terrorist list simply a list of “bad guys” or political enemies, unique to each country? To what extent are there objective and transparent criteria behind the designation? Can the United States still lead on global security issues with such distinct priorities compared to its allies? Does it want to? Regarding the future of designation, research tells us that sanctions work better when they are multilateral – generally, the more parties trying to punish an entity or prevent its actions, the more effective it will be. Thus, coordination among countries on terrorist designation is likely to be valuable. But global counter-terrorism will be difficult to sustain if countries’ priorities continue to separate.

This article represents the views of the author(s) solely. ICCT is an independent foundation, and takes no institutional positions on matters of policy unless clearly stated otherwise.

Photocredit: Mark Van Scyoc/Shutterstock