Vengeance and retribution are central motivations for supporting or joining terrorist groups. One need to look no further than the Islamic State-Khorasan Province (ISKP) who on 9 May 2024 announced a global “massacre of Jews and Christians in retribution for” the Israeli military entering Rafah. The role of vengeance and retribution in motivating violence is not new. As Homer wrote in The Trojan Wars, the great warrior Achilles returned to the battle not for glory or victory, but for vengeance – to make King Hector pay for the death of his friend, Patroclus.

It is a standard practice for terrorist group propaganda to use narratives of vengeance, anger, and retribution for government repression. Vengeance plays a critical role in some individuals’ choice to join or support a group. Government repression creates desires for vengeance and retribution because it creates both physical and psychological harm and victimisation. In turn, these emotions can trigger or strengthen individuals’ radicalisation processes, motivate support for opposition actors and movements, and cause individuals to pick sides in a conflict rather than remain neutral. In response to government repression, “the apathetic become polarised, [and] the reformers become radicalised.”

At the heart of these causal mechanisms are repression events. That is, while consistent systematic human rights abuses denote a regime as repressive, all governments are at risk of deploying tools of repression in response to specific threats, dissident events, or civilian actions. The latter are repression events, i.e., individually definable and observed occurrences of repression. Repression events provide focal points for political entrepreneurs, non-state actors, and terrorist groups to craft their propaganda around. Repression events take place in all countries, regardless of regime type, authoritarian practices, and respect (or disrespect) for human rights. For example, my research shows that in approximately 14.1 percent of protests across the globe, governments responded with repression. Importantly, 24.6 percent of the repression was committed by strongly democratic countries.

Repression events can push fence-sitters away from the government and toward opposition actors, thereby helping grow their support base, rank and file members, and potentially violent activists. But too often our collective research stops short of how non-state actors, such as terrorist groups, employ violent tactics and strategies to attract newly aggrieved and vengeful individuals in response to repression events.

It is unlikely that non-state actors observe government repression and violence and sit back, relax, and wait to see if aggrieved individuals pick their group or another group. Rather, they are motivated to act and advertise themselves as the right or best group to join to exact revenge and appease desires for vengeance and retribution. Yet, our understanding of how terrorist groups adapt their violent tactics and strategies in response to new opportunities to radicalise, recruit, and mobilise supporters is languid and significantly underdeveloped.

My European Research Council funded project – Terrorist Group Adaptation Patterns & Lessons for Counterterrorism (TERGAP) – addresses this issue by exploring how government repression events trigger short-term adaptations in terrorist group violence. TERGAP theorises that terrorist groups’ make strategic short-term changes in attack target selection following government repression to attract support from aggrieved and vengeful individuals. Identifying these strategic adaptations in terrorist attack patterns improves two fundamental limitations in terrorism studies – understanding terrorist groups’ strategic calculus and attack target selection.

Connecting Repression & Terrorism

Repression can increase the frequency of terrorist attacks, boost recruitment, and trigger radicalisation. It does so by generating anger, hate and humiliation, denigrating individuals’ or a group’s status and values, causing some dissidents to alter their self-perception to now see themselves as radicals, and reducing societal support for the government which increase the likelihood of active dissent. Repression creates psychological, physical, and economic damage rousing outrage, vengeance, and desires for justice as aggrieved individuals seek to punish the state.

These processes are foundational to the terrorism strategy of provocation, which aims to provoke retaliation that punishes innocent civilians and not only the perpetrating terrorists. The objective is to use the resulting anger, victimisation, and desires for vengeance and retribution to boost radicalisation, recruitment, and mobilisation. But connecting terrorist goals and behaviors in this strategy relies on underspecified and heterogenous causal mechanisms linking more terrorist violence or attacks to increased support. Associating more violence, in general, with more support or recruits overlooks that recruits are attracted by selective incentives and not necessarily or simply by more violence.

Instead, terrorist groups can execute strategic short-term changes in their violent tactics and adapt to new opportunities to provide selective incentives and fulfil potential supporters’ psychological needs. One salient selective incentive is the opportunity to fulfil the desire for vengeance for government repression. Research shows that terrorist groups change their attack patterns toward or away from civilian and government targets to mobilise support. But their violence is more flexible than this. Terrorist groups can advertise opportunities to exact revenge and retribution by strategically attacking and punishing the government agents or organisations responsible for perpetrating repression events. For example, in February 2024 and September 2022, Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin vowed revenge and claimed attacks against the Malian Armed Forces and Russian Wagner Group for a civilian massacre. In September 2022 ISIS also justified suicide attacks near al- Hawl refugee camp as revenge for Muslim women held there. In short, terrorists can implement a strategy of retribution.

As a research field, terrorism studies have largely overlooked how target selection is influenced by strategic choices and adaptations in response to new opportunities to radicalise, recruit, and mobilise support. As a result, our understanding of target choice is not well connected to strategic decision-making and behavioural motivations. If terrorist groups can adapt their violence to new opportunities to manipulate potential supporters’ psychological needs and thereby maximise an attack’s recruitment and support building benefits, then short-term changes could enable long-term survival. Identifying and analysing terrorism as a strategy of retribution is therefore essential for successful counterterrorism.

The strategy of retribution and underlying short-term adaptations are particularly important in domestic terrorism because these attacks can function as direct responses to government repression events and gain publicity, recruits, and attention to grievances because attacks are about both the target and the audience.

Analysing the Strategy of Retribution

To analyse a strategy of retribution in domestic terrorism, I use event coincidence analysis (ECA) because the methodology identifies causation by measuring temporal patterns between types of events and calculating whether one type of event triggers the other. This is done by measuring and correlating the time between events and the frequency of overlapping events. Using these measurements, ECA mathematically defines the strength, direction (precursor and trigger), and temporal duration of causal patterns by identifying variations that “are far beyond chance” Though rarely used in terrorism studies, ECA is more common in geology, neurology, and climate sciences and it has been used in the social sciences to analyse voting patterns and triggering effects of climate disasters on armed conflict onset.

For the analysis, I use the Mass Mobilisation Project and Global Terrorism Database to explore how government repression of protests (one type of repression event that includes beating, shooting, or killing protesters) influences domestic terror attack target selection per month in countries across the globe (except the U.S. and Israel which are not included in the protest-response data) from 1990 to 2017.

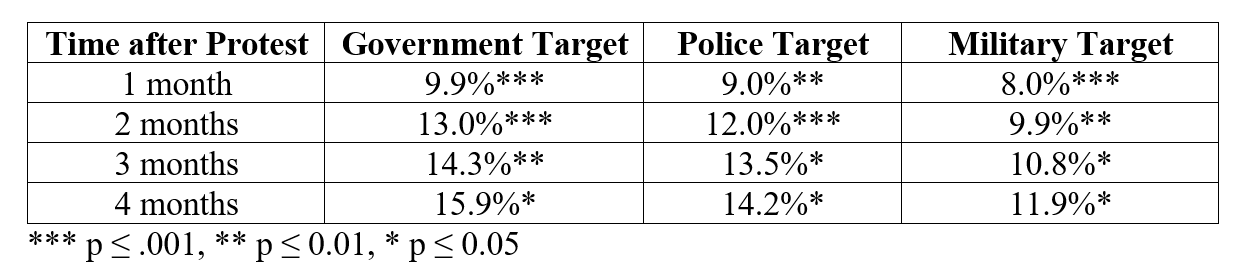

The results confirm that in instances where protesters are repressed (whether or not protesters themselves were violent or non-violent) increases the risk of domestic terrorism, but this increased risk varies depending on the potential terrorist attack target. Within one month of protest repression, trigger coincidences for domestic terrorism are identified for 9.9 percent of attacks against government targets, 9 percent of attacks against police targets, and nearly 8 percent of attacks against military targets. When extending the analysis to two months following protest repression, the trigger coincidence rates increase, respectively, to 13 percent, 12 percent, and 9.9 percent. These changes represent 31.3 percent, 33.3 percent, and 23.8 percent increases in the risk of attack for each target type. The growth rate slows each month, and the triggering effect is not statistically significant more than four months after protest repression. [1]

The table below shows the statistically significant trigger rates per attack target type, which indicate that retribution creates a short-term increased risk.

Table 1: Percent of Domestic Terrorist Attacks per Month Triggered by Repression of Protests (both Violent and Non-Violent Protests)

Protest Characteristics & Trigger Rates

Not all protests are the same. While the majority are non-violent, some turn violent. Repressing violent protests may be perceived differently than repressing non-violent protests. If perceptions of government abuse, morality, and justifications for repression vary depending on protesters’ actions, then desires for vengeance and retribution could also vary. The second scenario is, if protests are violent, there may be a pre-existing group of individuals ready to engage in higher-level violence like terrorism or more susceptible to terrorist groups’ recruitment and radicalisation efforts.

When protests are violent

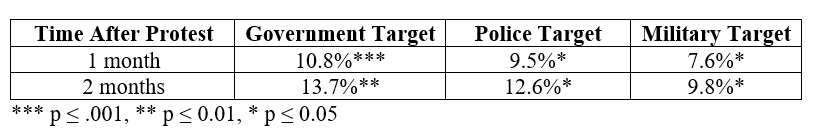

In instances where a protest was violent, then repression from state actors triggers an increased risk of domestic terrorism. Within one month of protest repression, trigger coincidences for domestic terrorism are identified in 10.8 percent of attacks against government targets, 9.5 percent of attacks against police targets, and 7.6 percent of attacks against military targets. When extending the analysis to two months following protest repression, the trigger coincidence rates increase, respectively, to 13.7 percent, 12.6 percent, and 9.8 percent. These changes represent 26.9 percent, 32.6 percent, and 28.9 percent increases in the risk of attack for each target type. Beyond two months after a protest, the triggering effect of repression is no longer statistically significant.

Table 2: Percent of Domestic Terrorist Attacks per Month Triggered by Repression of Violent Protests

This suggests that when governments meet violence with violence, it appears to trigger an escalatory action-reaction cycle that increases the threat of domestic terrorism and therefore decreases overall public safety and security. The effect is an immediate increase in domestic terrorism threat, but one that does not appear to grow exponentially over time. Gaining this understanding is invaluable for risk assessment, crisis response, and security planning. When governments are confronted by violent protests, response options are likely limited to use of force and potentially repressive tactics when restoring public order, especially when safety is the immediate concern. This is a challenging conundrum for governments to navigate.

When protests are not violent

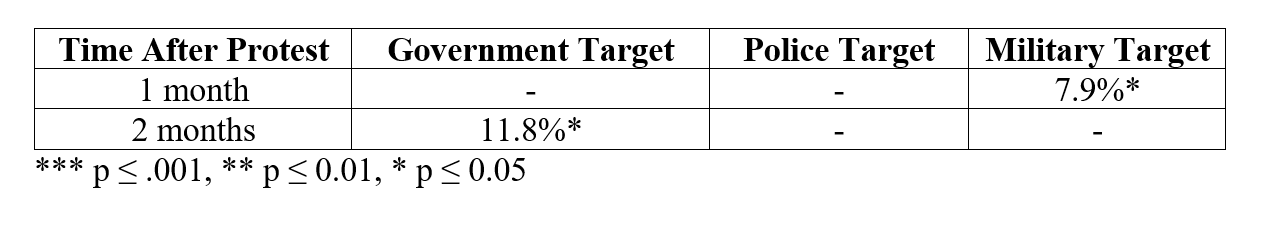

If the protest was non-violent, repression by the government has a minimal effect on the domestic terror threat or risk. While repression of non-violent protests is often unjustified, the analysis does not find a consistent statistically significant trigger effect on domestic terrorism risk. The risk of domestic terrorist attacks on government targets increases two months after this type of repression event. Whereas for military targets, the increased risk is immediate and lasts for 30 days following repression.

Table 3: Percent of Domestic Terrorist Attacks per Month Triggered by Repression of Non-Violent Protests

Discussion

Thinking about domestic terrorism as a strategy of retribution can help researchers better understand variations in terrorist attack tactics, group strategy, and linkages between government and dissident behavior. It also provides new evidence that domestic terrorism is sensitive to changes in government behaviour, in particular to protest repression.

It also allows analysts, practitioners, and policy-makers to anticipate and counter domestic terrorist threats and advise governments on potential consequences of their interactions with opposition movements, activists, and protesters. In general, repression events trigger an increased risk of being targeted in a domestic terrorist attack. This heightened risk level appears to be a relatively short-term threat. After four-months, a protest repression event is not a statistically significant trigger of increased domestic terrorism.

The results demonstrate that there are substantial differences between violent and non-violent protests that warrant researchers’ attention. Repression of non-violent protests has a small and inconsistent effect, whereas repression of violent protests consistently and systematically increases the threat of domestic terrorist attacks. Once violence is used, evolving from, for example, throwing bricks at security officers to engaging in a terrorist act, is a much ‘smaller’ escalatory step then, for example, marching down a street carrying a sign and chanting protest slogans to engaging in a terrorist act.

Funded/Co-funded by the European Union (ERC, TERGAP, 101116436). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them

[1] A more expansive write up and discussion of analysis and results will be presented at the European Political Science Association annual conference in July 2024.

This article represents the views of the author(s) solely. ICCT is an independent foundation, and takes no institutional positions on matters of policy unless clearly stated otherwise.

Photocredit: CHOKCHAI POOMICHAIYA/Shutterstock