After years of rumours, Syrian jihadist group Jabhat al Nusra is expected to sever its longstanding affiliation with al Qaeda at any moment.

As news of the impending split broke, many questions arose: Was it simply a smokescreen? Would al Qaeda still be pulling al Nusra’s strings? Won’t al Nusra still represent an extremist, violent ideology?

Healthy skepticism is definitely called for, but this extraordinary development is far from inconsequential. Even if the ideology remains the same, even if al Qaeda leader Ayman al Zawahiri continues to influence al Nusra’s ranks and its leaders, the shift in allegiance will reverberate around the globe.

The break formalises a dynamic that has been apparent for some time – al Qaeda’s affiliates have become less and less global, and more and more local. The vision of al Qaeda as one big thing has given way to the reality of multiple al Qaedas – in Syria, Yemen, Northwest Africa, East Africa, and the Indian Subcontinent. The affiliates increasingly cater to local concerns and local politics. Even before the break, al Nusra cited instructions from Zawahiri to cease any efforts to attack the West.

Of all the affiliates, al Nusra is best positioned to enjoy the benefits of independence.

Whatever skepticism and suspicions Western analysts and Syrian rebels rightly harbour about the split, some in the Middle East will be happy to take it at face value. Al Nusra functions within a highly diverse coalition fighting the Assad regime, and the separation from al Qaeda will enhance its ability to form alliances, despite lingering suspicions about its ultimate agenda. The break will also legitimise fundraising by Gulf donors and the states that regulate them, to a greater or lesser extent.

More broadly, this marks the beginning of the end for the global al Qaeda brand. Consider the next largest affiliate, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. Aside from personal loyalties within its leadership, AQAP has little motivation to maintain its affiliation. For about five years already, AQAP has shifted many activities away from the al Qaeda brand and repositioned them under the name Ansar al Sharia.

This move was purely cosmetic, but it is difficult to articulate the benefits AQAP receives from al Qaeda affiliation at this stage in the game. A formal break would strengthen its position in terms of local support, as well as providing some degree of insulation from international attacks. AQAP’s commitment to attacking the West – a key element of what makes an affiliate “al Qaeda” – has been persistent relative to its siblings, but also superficial, with token resources devoted to extremely sporadic attacks outside of Yemen and Saudi Arabia.

For the weaker members of the al Qaeda coalition -- al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and Somalia’s al Shabab -- the benefits of separation are less pronounced, but the benefits of staying are also ambiguous. If the centre does not hold, they may peel off, or they may continue to enjoy their current levels of significant autonomy. The last remaining affiliate, al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent, is likely closer to the core group, should Zawahiri or his successors wish to continue al Qaeda Central as an operational unit, which is not necessarily the case.

The original al Qaeda was ill-suited to directly fight a global jihad under its own name and organisational structure. For more than a decade prior to September 11, 2001, it shunned the spotlight and executed a disciplined mission statement of providing other groups with support, advice and operatives with expertise. It gradually transitioned into carrying out its own infrequent attacks.

After September 11, this approach became untenable, but the central organisation still commands some resources. After 15 years and dramatic changes in the jihadist landscape, today’s al Qaeda could conceivably revert to something like its pre-September 11 model – an underground actor that operates behind the scenes, lending professionalism to other jihadist organisations through training, money or by providing operatives. The professionalisation of jihadism over the last decade may render this approach superfluous, but it is could be a recipe for survival in the near-term.

While the central organisation failed as a warfighting machine, it has successfully planted seeds of conflict around the world. Stepping back from an overt leadership role could play to the strengths of the institutional leaders who still survive. And the so-called Khorasan Group in Syria, a cadre of senior al Qaeda operatives focused on terrorism, could fill a niche similar to the operational arm of the original organisation, as a relatively small unit detached from al Nusra (at least nominally) and focused on terrorism rather than insurgency.

Beyond all of these issues lie significant questions about the future evolution of jihadist ideology and strategy. The split does not signal that al Nusra seeks to moderate its extremist views or that it has abandoned its desire to create an Islamic emirate governed by an extreme interpretation of Shariah law.

But the break creates new evolutionary pressures on al Nusra to adapt to its local context, while reducing pressure to conform to a global ideology. The split from al Qaeda is an explicit concession to the primacy of local politics. In the face of considerable and justified skepticism, al Nusra will have to prove through its actions over time that the break is more than a distinction without a difference. If the change in brand does not correspond to a change in script, the gambit will ultimately fail. Al Nusra will have to find ways to visibly and substantially differentiate from al Qaeda.

Evolution will not necessarily lead to a more centrist and less extreme organisation. Nusra’s leaders may simply bide their time, waiting to revert to form, or the fluid situation on the ground could lead it in a darker and more violent direction. But an influx of local participants and local leadership could conceivably lead it in a more moderate direction… eventually. In the short-term, little is likely to change on the ideological front.

Finally, the split comes during an interesting and chaotic time in the competition between al Qaeda and the so-called "Islamic State" (IS), the original breakaway faction.

Starting in 2014, IS began chipping away at the unity of the global al Qaeda movement and ideology, winning both defectors and the lion’s share of new recruits. IS has risen to become the most dangerous current threat to global security, eclipsing its parent in many respects even as al Nusra and AQAP continued to quietly build support and claim territory.

IS has grown to fit the model that al Qaeda could not – a populist extremist movement with a substantial presence in locations around the world, including both insurgent and terrorist branches. Even as it has lost important territory in Iraq and Syria, it has flexed its muscle abroad, with directed terrorist attacks in Europe, Bangladesh, Afghanistan and beyond. Al Qaeda Central held together in the face of this challenge, but imperfectly.

After the split, al Nusra may benefit in its efforts to compete with IS for foreign fighters and the hearts and minds on the ground in Syria. Other affiliates could enjoy similar benefits from separation as they struggle with local challenges from IS and slowly asserting themselves as strong, credible alternatives to IS. But the flip side of this dynamic is the weakening of the global al Qaeda brand – as it loses its most successful affiliate – and a perception of retreat, both of which aid the IS propaganda narrative, predicated on an image of strength.

The ultimate outcome will play out over time, and the shape of what follows is not yet clear, except that it undoubtedly heralds a change.

Whatever the long-term consequences, the breakup sends a powerful message about the limits of al Qaeda as a brand and an organisation, and it opens the door for other pragmatically minded affiliates to go their own way.

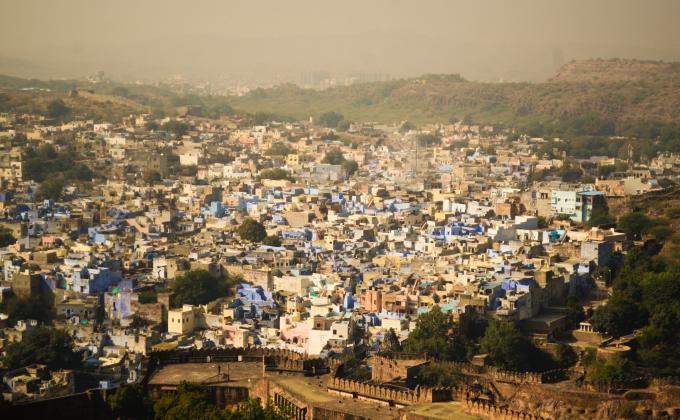

Photo Credit: Jamie Dettmer/Voice of America