According to the Global Terrorism Index 2018 (GTI), released in November 2018, South Asia ranked second in regions most affected by terrorism-related attacks and deaths in 2017. The 2018 GTI also notes that three countries in the region—Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India—are amongst the top ten countries most impacted by terrorism worldwide. The GTI, and other similar assessments, reveal that major terrorist groups operating in the region include al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and the Khorasan Chapter of Islamic State (ISK) in Afghanistan and Pakistan; the ultra-left Maoists and the Lashkar-e-Tayyiba in India; and various homegrown Islamist extremist groups affiliated with al-Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS).

Although the annual GTI is revealing in terms of terrorism trends, the index offers few insights into counterterrorism responses from countries around the world. Instead, other periodic assessments, such as the Armed Conflict Survey, published yearly by the International Institute for Strategic Studies, the Country Reports on Terrorism, an annual publication by the U.S. Department of State, and various think tank reports provide useful data on how governments around the world are adapting to the evolving threat of terrorism.

Conventional wisdom suggests that since the ‘global war on terrorism’ began in 2001, the militarized counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations carried out by the U.S., NATO, and Afghan national security forces in Afghanistan, and by the Pakistan Army in federally administered tribal areas have attracted huge international attention. The Indian Army’s longstanding deployment both in the pre-, and post-9/11 era in Kashmir and north-eastern states to suppress secessionist terrorism has also drawn widespread attention. In other South Asian countries, military forces have launched sporadic operations to maintain internal security, or to suppress left-wing insurgency or ethno-nationalist insurgency.

This essay argues that aside from military forces, paramilitary police units (PPUs) are emerging as a salient feature of the South Asian counterterrorism regime. In spite of this, the growth of PPUs remains a relatively under-explored phenomenon. This lacuna is addressed by presenting findings from an ongoing study on South Asian terrorism trends and counterterrorism strategy. This essay is divided into several sections. First, it provides a brief description of the differences between civilian police units and PPUs. Next, it analyses the post-9/11 context in which new PPUs were created and deployed. Third, it discusses the complex and shared operational spaces in which PPUs are deployed. The concluding section discusses future implications for South Asian PPUs.

There are compelling reasons for studying the role of PPUs in counterterrorism. Such analyses allow an exploration of the extent to which, in South Asia, the war model of counterterrorism is increasingly becoming popular, albeit in amended form, leaving behind the criminal justice and public health models of counterterrorism. For counterterrorism practitioners, the increasingly frequent use of PPUs raises questions of efficacy; are PPUs a viable alternative to military forces or other, less overtly kinetic approaches to dealing with this form of political violence? This ICCT Perspective highlights several aspects of PPUs that touch on these debates.

Understanding Paramilitary Police Units

Although civilian police and military forces maintain sharply different roles in the fight against terrorism and organized crime, this distinction is often blurred by the creation of PPUs. Well-known examples of which include the American SWAT, the Italian Carabinieri, and the French Gendarmerie. The list of major South Asian PPUs include ANCOP and CRU in Afghanistan; RAB and CTTC in Bangladesh; ATS, COBRA, and RAF in India; CTF and SCU in Pakistan; and STF in Sri Lanka. The smaller countries in the region also have their own PPUs: SRPF in Bhutan, NPFS in Nepal, and SOD in Maldives. These PPUs are often referred to as elite police units or special police units, but in what ways are PPUs different from civilian general-duty police units?

Police militarisation expert Peter Kraska identifies four distinct characteristics of PPUs—material, cultural, organisational, and operational—that set them apart from general-duty police units. The first – material – concerns weapons and equipment. While civilian police units primarily carry defensive weapons and equipment, militarized police units emphasize carrying offensive weapons and technologies. Second, unlike the civilian police personnel whose appearances, beliefs, and language aim at preventing crime in the society, elite police forces adopt military-style appearances, beliefs, and cultures. The third difference relates to how the police units are organised; general-duty police units usually have police-station based jurisdiction, whereas militarized police units prefer battalion-sized formations. Finally, operationally, civilian police prioritize a defensive posture for the prevention of crime and the maintenance of order whereas the elite PPUs demonstrate an offensive posture in gathering intelligence and handling high-risk operations.

Global War on Terrorism, Domestic Circumstances, and South Asian PPUs

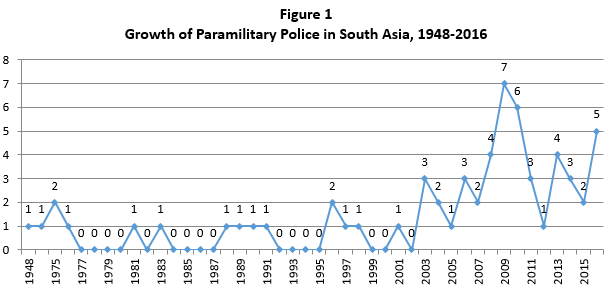

Drawing on Kraska’s thesis on the attributes of paramilitary police units, my research shows that there are at least 62 PPUs in South Asia: 35 in India, nine in Pakistan, eight in Bangladesh, four in Afghanistan, and the other six in Bhutan, Maldives, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. Reflecting the global impact of the 9/11 attacks and the ‘war on terror’ that followed, of these 62 South Asian PPUs, 47 (76%) were established in the post-9/11 period, while only 15 (24%) were established pre-9/11. Figure 1 illustrates this historical trend by showing the number of PPUs established in specific years. An important question is whether it is transnational threats or internal pressures which have most contributed to the proliferation of South Asian PPUs.

Source: author’s database.

Among the 47 new PPUs established in the post-9/11 era, 28 are in India, six in Pakistan, five in Bangladesh, four in Afghanistan, two in Bhutan, and one each in the Maldives and Nepal. Sri Lanka did not establish any PPU in the past three decades, although its armed forces have maintained a heavy-handed approach to suppressing the Tamil insurgency.

In order to understand how external influence, domestic imperative, or a combination of both has shaped their growth, one needs to look at the deployment of PPUs in combating domestic and transnational terrorist groups. I argue that external influence, measured by the presence of transnational extremist groups in a country, and the U.S.-led counterterrorism strategy, determined the growth and expansion of PPUs in Afghanistan and Pakistan in the post-9/11 era. In other South Asian countries, domestic factors have played a much larger role in shaping the growth of PPUs, or lack thereof.

In Afghanistan and Pakistan, the newly established PPUs have a direct role in combating transnational terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda, ISK, and the Taliban. In Afghanistan, PPUs are an integral component of the Afghan National Security Force (ANSF). The ANSF was formed as part of the U.S.-led coalition’s ‘transition’ strategy to indigenise the counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations against both the foreign al-Qaeda militants and the local Taliban militias. After the withdrawal of a large majority of U.S. and NATO forces in 2014, the ANSF, including its PPUs (e.g. ANCOP [15,000 personnel] and GDPSU [1,000 personnel]), acquired a major role in combating al-Qaeda, the Taliban, and the newly emerged ISK. The fight against al-Qaeda, IS, and their local affiliates has similarly driven the growth of elite police units in several Pakistani provinces. In 2010, the Sindh province formed the SSU (3,000 personnel); in 2014, the Punjab province established CTD (1,200 personnel), and the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province created SCU (150 personnel). As violent extremism perpetrated by homegrown and transnational militant groups increases in Pakistan, these newly formed PPUs have grown more visible in the country’s law enforcement landscape.

The context is sharply different in other South Asian countries. For example, in Bangladesh, a country with a predominantly Sunni Muslim population, it is concerns over the influence of al-Qaeda and ISIS on local militants, rather than the actual presence of these organizations, that has played a decisive role in creating and tasking the major PPUs. For instance, with an approved strength of nearly 10,000 personnel, RAB was formed in 2004 primarily as a response to deteriorating law and order. However, soon after its establishment, RAB found a counterterrorism role fighting against JMB and HuJI-B, the top two terrorist groups established by the Bangladeshi-origin veterans of the 1979-1989 Afghan War.

Since 2013, al-Qaeda’s local partner Ansar al Islam and the ISIS-affiliated Neo-JMB have emerged and with this emergence have unleashed a new wave of terrorism targeting online activists, alleged non-believers, and foreigners. It is in this context that the Bangladesh Police established CTTC as an intelligence-focused PPU in 2016 and expanded it in 2017 into a full-fledged national unit with 600 personnel. The CTTC not only has a bomb disposal unit and a cyber crime monitoring unit, but also a roughly 100-man strong SWAT team that was constituted in 2009 under Dhaka Metropolitan Police, and was later brought under the command of CTTC. After self-declared ISIS sympathizers in Bangladesh executed a high profile terrorist attack in the Gulshan diplomatic zone’s Holey Artisan café in 2016, the Bangladeshi government established another new PPU—the ASF—with 350 personnel to enhance the security in the diplomatic enclave.

For India, it is not violent Islamist extremism but concerns over Maoist insurgency and ethnic separatist movements that have long shaped the growth of PPUs. As a result, almost all of India’s 29 provincial states and the national capital territory Delhi have formed Anti Terror Squads (ATS). These and other elite police units vary in size and operate as PPUs under the authority of provincial police services. Only the state-level police forces in Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Chhattisgarh, Manipur, Maharashtra, Meghalaya, and West Bengal have large commando police units (each having 1000+ personnel), whereas Tamil Nadu and Kerala have medium-sized (500-1000 personnel) PPUs, and the rest have smaller militarized police units (less than 500 personnel). Among the provincial-states with large PPUs, Maharashtra not only has a huge population but also a long history of being targeted by organized crime syndicates and Kashmir-focused militant groups such as the Lashkar-e-Tayyiba, the main perpetrator of 2008 Mumbai attacks. The ultra-Maoist insurgency in poverty-stricken areas and the challenges of riots and crowd-control have also shaped the formation of some of the largest national PPUs such as (10,000 personnel) and (8,000 personnel), both operating under the Central Reserve Police Force.

In the rest of South Asia, PPUs also operate in various contexts not related to the U.S.-led global War on Terrorism. Sri Lanka established the STF (6,000 personnel) in 1983 to fight Tamil separatists; Maldives formed the SOD (250 personnel) in 2006 to ensure internal stability and enhance regime control; and Bhutan created SRPF (strength unknown) in 2011 to fight Maoist rebels. The Nepal Police has long maintained a Flying Squad with about a dozen operatives who are used for various internal security purposes including the Maoist rebellion.

In summary, both external influences and domestic factors can explain the growth of PPUs in South Asia. The decisive impact of external influences is most obvious in the case of Afghanistan and Pakistan, but the institutional preference of the civilian police services in the region to expand their militarized units remains a major driver of PPUs in all other states.

Complex and Shared Operational Space

In the post-9/11 era, the conventional military forces, paramilitary border forces, and Special Operations Forces (SOFs) in Afghanistan and Pakistan have played a major role in the fight against terrorism. Hence, the PPUs in both countries have often shared a complex operational space. Although in other South Asian countries the PPUs have primarily dominated the domestic law enforcement environment, there are several circumstances and unique operational experiences that allowed the military-led SOFs to take the lead in counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations, leaving PPUs to play a largely supportive role. The Indian National Security Guard's counterterrorism response to the 2008 Mumbai attack in India and the Bangladeshi 1st Para-commando battalion’s hostage-rescue operations in response to the 2016 Holey Artisan attack are two such cases of SOF taking the lead. In most other instances, PPUs share responsibilities for intelligence, covert actions, and counterterrorism operations with various civilian and military-controlled agencies. As lone wolf or single-actor terrorism is yet to emerge as a major threat in South Asia, and homegrown terrorists maintain varied levels of connection with transnational groups, it is important that PPUs adapt to the evolving threat landscape and improve inter-agency collaboration.

Implications for Future

The territorial defeat of ISIS in Iraq and Syria will have repercussions for the terrorist threat-landscape in South Asia, as well as the rest of the world. PPUs will continue to operate in a landscape marked by several distinct changes. In South Asia, these appear to be threefold. First, al-Qaeda in the Indian Sub-Continent (AQIS) and returning or returned foreign fighters with links to ISIS will likely compete with each other in a recruitment drive to draw new members to their movements. Second, home-grown militants and ISIS sympathisers, that either failed to join the group in Syria or Iraq or were advised by that organization to remain at home, will continue to form a threat of terrorist violence. Third, the threat posed by Maoist insurgents and ethno-nationalist groups who maintain varying levels of capacity to plan and execute terrorist attacks in their home countries. The terrorist tactics and their funding requirements are also transforming with smaller groups and individuals operating more independently or in loosely structured networks leveraging the use of small amounts of funds to conduct deadly attacks on a wide range of targets.

Heavily-armed PPUs will likely remain a key component in South Asian counterterrorism for the foreseeable future. South Asian CT practitioners will continue to rely on the use of hard power and brute force in addressing the threats of terrorism. An important question is whether the PPUs will operate in a culture of impunity or whether they will be held to account for any extrajudicial actions. This question arises for obvious reasons: State-controlled security forces, including PPUs, have often made excessive use of force, and most such instances have gone unpunished. Given the extent of the terrorist threat facing numerous South Asian countries, it is unlikely that non-militarized alternatives to preventing and addressing terrorism will be able to take precedence. The growth of PPUs outlined in this Perspective is thus a trend that is unlikely to change, at least in the short term. Nevertheless, steps should be taken to enhance PPUs compliance with international legal and humanitarian standards. This will not only enhance their legitimacy among the populations they serve, but also reduce the risk of ‘collateral damage’ or indiscriminate violence inadvertently fuelling the fire that these units were meant to douse.

Click here for the list of abbreviations used in this Perspective.