Three years have passed since the fall of ISIS at Baghuz and still over 7,300 children from across 60 countries are detained in the al-Hol and Roj camps in north-east Syria, managed by the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES). It is also three years since two grandparents initiated proceedings against France for their unwillingness to repatriate their grandchildren and daughter. This week, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) finally delivered its judgment, concluding firstly that France cannot be held responsible for the inhumane conditions in the camps, secondly that there is no general right to repatriation, and thirdly that France had failed to ensure proper safeguards in its repatriation decision resulting in a procedural violation of the rights of the children to enter their own country. This split applicability of extra-territorial jurisdiction of human rights will resonate through the policies and have ramifications for the fate of many European children held in north-east Syria.

The majority of the children were born there and are under the age of 10. Furthermore, another 800 young boys with alleged ties to ISIS ranging from the age from 10 to 18 years are held in detention centres often without criminal charges. The conditions in the camps and detention centres are deplorable with a lack of sanitation, food, health care and continued violence having led to the death of nearly 100 persons in 2021.

Several countries such as Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kosovo, Albania and more recently Kyrgyzstan have repatriated women and children for some time. However, in the past year several European countries started to repatriate women and children from the camps more actively. Germany and Denmark for example, jointly repatriated 37 children and 11 women from camps whereas the Netherlands has repatriated 5 women and 11 children, and are likely to repatriate more children in the coming months. Belgium repatriated 16 children and 6 women, Sweden 20 children and 10 women over the past year, and France recently repatriated 35 children and 16 women from Roj camp, marking this the first time that French adults have been repatriated from Syria.

This perspective provides a short overview of the number of children that have been repatriated and remain in the camps and then describes the current situation based on a recent interview conducted by ICCT with the AANES. The second section explains the main issues of the ruling of the ECtHR, the impact this has on the policy of European countries to repatriate the children that are still in the camps, and explores some of the challenges and options states face once the children are repatriated in terms of rehabilitation and reintegration into society.

Repatriation and Return Numbers from Select Countries

The past few years have seen an enduring reluctance from European countries to actively bring home their adult nationals, and in many cases even child nationals, from the camps. Most frequently cited justifications for this stance are domestic security risks supposedly posed by returnees, the argument that justice is better served in Iraq or Syria where witnesses and evidence can be found, and the narrative of the voluntary nature of the foreign ‘terrorist’ fighters (FTFs) travel, often in breach of national laws. With regard to children, it is often argued by states that it is inappropriate to separate children from their parents and that therefore neither will be repatriated.

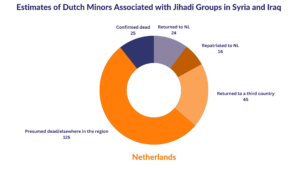

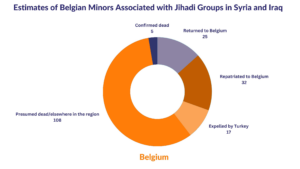

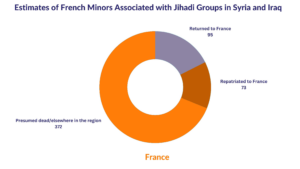

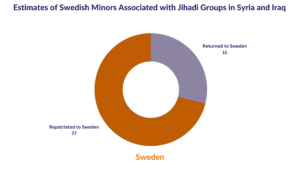

The below table from Rights & Security International gives an overview of those that have been repatriated from the camps since January 2019, and the subsequent graphs provide a more in-depth look into the scale of the challenge for five European countries as a means of highlighting the spectrum of eventualities that might be in store for remaining FTFs.

From the data observed we are able to make some broad estimates of how many children may remain in the AANES camps from the countries above.[6] These numbers derive from ranges given rather than known individual cases, therefore the figures should be read as indicative rather than exhaustive. It can be assessed from the above that around 60 Dutch children remain in the camps, whereas the figure for Belgium is somewhere between 12-17. For France there remains an estimated 150-170 children in the camps. For Finnish and Swedish children the figures are approximately 6-8 and 25-30, respectively.

Some trends can also be seen, and comparisons made amongst the countries. Firstly, the number of children that have spent time in the conflict zone from just the five EU countries listed in detail here is over 1,200. The majority of those were born in Syria and Iraq meaning they are under 10 years old. Secondly, the child repatriations to the five EU countries we detail here total around 174, fewer than 60 per year amongst the five countries combined since the fall of ISIS in Baghuz. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, in the EU countries we looked at in detail, child returns through unofficial channels, or by being sent back by third countries, are about equal to those facilitated through official government repatriation efforts. This is chiefly because most states only recently changed their policies and began repatriating children from conflict zones.

Many countries follow policies which allow for decision-making with regards to repatriation on a case-by-case basis, though the criteria on which these determinations are made are not publicly available. Considering more child repatriations are beginning to take place, low though the numbers may be, it will be necessary for the repatriating countries to ensure they have implemented rehabilitation and reintegration policies and measures that address the complex issues presented by child returnees in the short-, medium- and long-term. The trauma experienced and subsequent support needs of repatriated children will be informed by the conditions they were exposed to in the conflict zone and in the camps. Though individual experience will differ, the general conditions in the camps and rights violations suffered by the children there are broadly applicable and are set out in detail below.

Situation in the Camps

The question of repatriation of the remaining children from the conflict zone is one based in both ethical and legal considerations. The driving force behind these concerns are the dire conditions and security concerns that exist within the camps as well as the potential resulting infringements these conditions cause on the human rights of the children left there. In the section below we set out the reality of the conditions in the camps based on an interview conducted by ICCT with al-Hol camp administration. The conditions highlighted in this interview has also informed our assessment of which rights are currently being violated by European countries’ failure to repatriate their remaining children from the camps. This assessment, some of which is in line with the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (the Committee) 2022 communication of rights violations in the camps, is also set out below.

Population

The two camps run by the AANES, al-Hol and Roj camps hold around 60,000 people collectively, 12,000 of which are third-country nationals i.e., not citizens of Iraq or Syria. At present, in al-Hol Camp’s Foreign Person’s Annex alone, there are around 2,038 foreign families made up of around 7,600 foreign women and children of 58 different nationalities. Women and children from Europe, however, no longer live in al-Hol camp, they have instead been transferred to Roj camp which itself was reported in August 2022 to be made up of around 801 families and 2,506 individuals. Crucially, 50 percent and 55 percent of al-Hol and Roj’s population, respectively, are under the age of 12. The total number of children living in the two camps combined is estimated by the UN to be 40,000 which includes 18,000 Iraqi children. Some third-country boys are also placed in the Houri rehabilitation centre or are detained at other sites in north-east Syria about which less information is known.

In February 2022, the Committee concluded not only that the children left in the camps fall within the jurisdiction of the state party in question, in that instance France, but also that absence of diplomatic and consular representation in Syria does not constitute a decisive obstacle to repatriation considering previous repatriations have occurred and given that the AANES frequently reiterates its appeal for international cooperation on repatriation. Decisions taken to not repatriate remaining children violates the right against discrimination as the decision is considered to be motivated by the suspected terrorist activities affiliations of their parents. This right is further infringed when one considers the lack of consistency or permanent criteria explaining why orphans are deemed more eligible for repatriation than those accompanied by their mothers when all are equally subjected to the same violations of the best interests of the child. Additionally, continued detention infringes the children’s right to maintain family relations with their close relatives such as grandparents, aunts and uncles.

For those children born in the in previous ISIS-held Syrian or Iraqi territory, or within the territory and camps now governed by the AANES, refusal of states to repatriate and process them as citizens of their country violates their fundamental right to be provided with a civil status and a nationality, and their right to preserve their identity and relations with their family (Articles 7 & 8 UN Convention of the Rights of the Child).

Provision of basic welfare needs

Though water is available in the camps through pipelines and food can be purchased from shops in the camps run by external owners, the conditions in the camps are widely considered to be dire. Women receive money from their families through a camp office, and the women and children are also supported with dry foodstuffs like rice or other necessities like blankets by various NGOs or the AANES itself. There is no electricity in the camps, and phones are prohibited though battery-powered lights and ventilators are placed throughout. Healthcare is provided to al-Hol by external doctors who are available in the camp for six hours every day and detainees are transferred to a hospital in Heseke if surgery is required. This healthcare system is facilitated by NGOs like the International Committee of the Red Cross though camp administration has stated that the dental health system needs to be improved.

NGOs organised a school for children to attend in the Annex of al-Hol, but the camp administration state that most mothers refuse to allow their children to attend as a rejection of external influences which might challenge their ideology. As a result most children are educated along the lines of jihadist ideology by their mothers. Sanitary services were previously supplied by external personnel but the security situation in the camps has deteriorated to the point where it is no longer possible for them to work on site. Conditions of detention include inadequate heating, hygiene and sanitation, water, and food. It was claimed in our interview with the al-Hol camp administration that the home countries of the detainees do not provide them with any funding for the costs of food, water, healthcare, education, or sanitary services.

Continued prolonged and indefinite detention in the camps, where the children are severely lacking in health care, food, water, sanitation and education, and where there is a risk of indoctrination, was determined by the Committee to breach their right to have the best interests of the child as a primary consideration. Knowing of the conditions in the camps, the failure to repatriate constitutes a violation of the children’s right to the health and health services in that since states are allowing the abuses to continue. The lack of any formal or compulsory education structure in the camps also violates the children’s right to education.

Security

It is unclear precisely how many children have been victims of violence in the camps over the years but what is clear is that violence is extremely common. 371 children died in al-Hol camp in 2019 and 157 in 2020. Between January and August 2021, 62 children died in al-Hol from illness, accidents, and violence including at least three incidents of child murder. Further, it was reported in June 2022 that 106 murders occurred in al-Hol camp in just 18 months. Reports also estimate 300-350 boys being separated from their mothers by security services and transferred to other detention facilities without the prospect of further contact with their families. These security concerns are ongoing, as recently as September 2022, Syrian Democratic Forces uncovered dozens of ISIS operatives inside the camp acting as part of a major ISIS facilitation network and liberated four women found inside tunnels within the camps who had been chained and tortured.

Coupled with the lack of welfare needs laid out above, the security concerns amount to an abuse of not only the children’s right to life, survival, and development but also their right to be free from inhumane treatment and detention. Relevant to this violation is the fact that the children detained in the camps are held without any detention status and are subject to no local judicial proceedings. Further, exposure to the level of violence documented in the camps leave children open to risk of illness, injury, and imminent death, amounting to a violation of their right to protection from violence, abuse, and neglect.

The Committee concluded that the conditions in the camps pose an imminent risk to the lives of the children and constitutes cruel, inhumane, or degrading treatment. The right to have the best interest of a child as a top priority clearly is violated by the inaction of states. The nuances in the legal debate on the jurisdictional issues surrounding these rights is explored further below, but what is clear is that the rights under Articles 6 and 37 of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child are being violated and repatriation is the only means available to uphold any applicable positive obligations.

The legal debate on the extra-territorial jurisdiction

The main issue in the judgement relates to the extra-territorial scope of human rights. States are generally obligated to respect the human rights of those within their jurisdiction, i.e. on their territory. Although, there are exceptions to this, for example when a state exercises jurisdiction abroad through effective control of either the territory or exercises authority and power over an individual abroad (General Comment, No 31 § 10). Different factors are taken into account to determine whether a state exercises effective, territorial, or personal control. A clear distinction needs to be made between a substantive violation of the human rights and the procedural aspect of whether the state has jurisdiction and thus any human rights obligations can be attributed to the state. When a state has jurisdiction, it has a positive obligation to respect and protect the human rights.

In more recent years, another method of establishing jurisdiction might be emerging, focusing on control over rights. Therefore, when a state exercises effective control over the activities that cause the damage and the consequent human rights violation, it has jurisdiction. The discussion on the scope of extra-territorial jurisdiction has not yet been crystalised and will be a matter of debate in the coming years.

In the context of the repatriation of children from the camps in north-east Syria, it is now well known and confirmed by the Committee that the rights of children in the camps are violated. No country could claim not knowing how bad the situation is in the camps. The pertinent question is whether the state's jurisdiction in the current case meets the requirement of effective control and which factors are taken into account to make this assessment.

In this case, the Committee has reiterated its finding on admissibility ‘in the sense that the state party, by virtue of its nationality link with the children detained in the camps, the information it has on the children of French nationality held in the camps, and its relationship with the Syrian authorities, has the capacity and power to protect the rights of the children in question, by taking measures to repatriate them or other consular measures.’ Although the basis of jurisdiction on nationality has faced backlash, others note it is not meant for widespread application but for specific cases of children identified in camps.

The second criteria mentioned by the Committee is the capacity or capability of France to protect the rights of children in the camps must be connected with due diligence in international law. Due diligence relates to control – not over the persons – but over the harm that directly has an impact on human rights of the individuals. Due diligence is only applicable if a harm is reasonably foreseeable, and the state has the capacity to intervene. Due diligence is not a criteria to establish a jurisdictional link but to establish whether a state has the capacity. France has recognised the poor conditions in the camps and through the many reports is aware of how the rights of children are affected by the detention in camps. The AANES has communicated clearly that all foreigners should be repatriated and has worked with many states to facilitate the repatriation of their nationals. Recently France repatriated 35 children and 11 mothers, which clearly illustrates that France does exercise power and authority over individuals in the camps.

The European Commissioner on Human Rights and the Special Rapporteurs all note that France has an obligation to repatriate their nationals given they have proved this ability through repatriating other nationals from the area in question. Their view of positive obligations concurs with previous views from the Committee and other scholars. Furthermore, repatriation is essential in preventing trafficking, including of children.

The ECtHR has recognised that diplomatic or consular activities abroad, or when a state carries out law enforcement or judicial activities with the consent of a foreign country including detaining persons abroad, could establish jurisdiction. The UN bodies and regional courts tend to take a broader interpretation of extra-territorial jurisdiction, whereas the ECtHR has taken a more restrictive approach. It is perhaps unsurprising then that on the jurisdictional question, the ECtHR’s has not provided sufficient clarity.

The ECtHR had to determine whether the decision of France not to repatriate the children from north-east Syria violated their right to enter the country (Article 3 Protocol 4 to ECHR) and whether the conditions in the camps constitute ill-treatment (Article 3 ECHR). Firstly, the Court concluded that France has no effective control of the area and the fact that France has opened criminal proceedings against the mothers, does not establish a jurisdictional link to France. Furthermore, if initiating criminal proceedings would constitute a link, the ECtHR believes states could refrain from opening investigations.

The ECtHR made two distinct assessments on the jurisdiction and concluded that France was not responsible for the living conditions in the camps because it lacks jurisdiction. Neither the nationality, nor the capability of France to repatriate, nor the willingness of the AANES to cooperate are sufficient to establish such a link.

The ECtHR also found that there was no consensus at the European level in support of a general right to repatriation, nor was there any obligation in domestic or international law for states to repatriate under Article 3 § 2 of Protocol No. 4. With respect to the right to enter one’s own country, ECtHR concluded that nationality alone is not an autonomous basis of jurisdiction, but recognised that this right is relevant in the context of countering terrorism and that the specific circumstances should be taken into consideration to determine jurisdiction. The number of official requests, the living conditions in the camps, and the form and length of detention are some of the factors that create a jurisdictional link with France, as they are deemed to have done in this case.

The ECtHR did, however, conclude that the decisions on repatriation need to be taken with appropriate safeguards against arbitrariness. In practical terms, this means that each decision must be considered, and communicated, on the basis of the individual facts of that case, the decision must be subject to independent review, and the best interests of the child must be specifically considered in the decision. ECtHR considered that France had failed to do this and thus violated the right of women and children to enter their national territory. France is, therefore, obligated to reconsider the repatriation application in question with the above safeguards in place, which is seen by some as a symbolic victory.

Conclusion

The ruling of the ECtHR is a double-edged sword that leaves the children and their mothers in limbo. The Court takes a narrow approach in concluding that the conditions in the camps cannot be attributed to France as a result of their repatriation decisions, whereas both action and omissions of a state should be taken into account in determining whether a country can be held accountable. Clearly, by not repatriating, France is prolonging the ill-treatment of the children in the camps. The harm inflicted on the children is foreseeable and France has the ability to change this. On the right to enter their own country, the ECtHR concludes that there is extra-territorial jurisdiction, adding to the confusion and fragmentated approach the ECtHR is taking on the extra-territorial application of human rights. The right to enter one’s own country is violated by France, not on substance but on procedure. In other words, while there is no right to repatriation, the process of making the repatriation decision was flawed. Additionally, states are now left with broad discretionary powers to establish the independent review by a body capable of assessing the lawfulness of the decision, though this does not need to be a judicial authority.

The Secretary General of the United Nations, numerous UN Special Rapporteurs, the Council of Europe, the European Commissioner for Human Rights, and the European Parliament have indicated that the ‘best interest of the child’ should be the primary consideration in the repatriation, rehabilitation, and reintegration of children from the conflict zone. For the 7,300 children still detained in the al-Hol and Roj camps, many of which are citizens of European countries, the ECtHR’s decision provides them with some hope regarding to procedural safeguards in the decision-making process, but little else. They still have no guarantee of repatriation leaving them in the camps that are widely recognized as inhumane.

Child returnees may face an array of health problems, often suffer from multiple traumas, and may have mental health problems that can manifest years later. The children lack proper education and have been deprived of a normal childhood. Furthermore, the children may have witnessed or participated in violence and been exposed to indoctrination and radicalisation. From our own research these and other challenges demonstrate the need for a comprehensive long-term policy for the management of child returnees. Despite the drawbacks in the ECtHR decision, it should hopefully prompt France and other countries to repatriate all the children with their mothers, and invest in developing a rights-based policy for the management, rehabilitation, and reintegration for child returnees.

[1] The sum of those who, according to the Dutch General Intelligence and Security Service, are “among jihadist groups in northwestern Syria” (70), “possibly elsewhere in Syria” (30), and “staying in Turkey” (25). https://www.aivd.nl/onderwerpen/terrorisme/uitreizigers-en-terugkeerders; https://www.rightsandsecurity.org/action/resources/global-repatriations-tracker.

[2] https://www.rightsandsecurity.org/action/resources/global-repatriations-tracker; https://www.brusselstimes.com/79097/five-belgian-new-borns-have-died-in-camps-since-the-fall-of-isis; Thomas Renard and Rik Coolsaet, From Bad to Worse: The Fate of European Foreign Fighters and Families Detained in Syria, One Year after the Turkish Offensive [Policy Brief] (Egmont: Royal Institute for International Relations, 2020);

[3] https://www.rightsandsecurity.org/action/resources/global-repatriations-tracker; https://www.hrw.org/news/2022/07/13/france-repatriates-51-women-and-children-camps-syria; https://tribune.com.pk/story/1832767/france-plans-repatriate-children-militants-syria; https://www.lefigaro.fr/flash-actu/2017/02/02/97001-20170202FILWWW00230-700-mineurs-francais-vont-rentrer-de-syrie.php

[4] https://valtioneuvosto.fi/en/-/mfa-finland-repatriates-five-member-family-from-syria; https://julkaisut.valtioneuvosto.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/160777/SM_13_2018.pdf; https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-59577375

[5] There are no numbers available on how many children have left Sweden, so this chart merely presents the children whose whereabouts are known at this point. https://www.rightsandsecurity.org/action/resources/global-repatriations-tracker; https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/pdf/when_am_i_going_to_start_to_live_final_0.pdf/

[6] There is an inconsistency in the type and detail of data that is available from each country. The Netherlands for example indicates the number of children that are with jihadi groups in Northwest Syria, elsewhere in Syria, and in Turkey but no other country specifies this. Not all countries give an indication as to how many of their child citizens have died during the conflict. Finally, Belgium is the only country to specify the difference in the method of return.

This publication represents the views of the author(s) solely. ICCT is an independent foundation, and takes no institutional positions on matters of policy unless clearly stated otherwise.

Photocredit: Trent Inness/Shutterstock