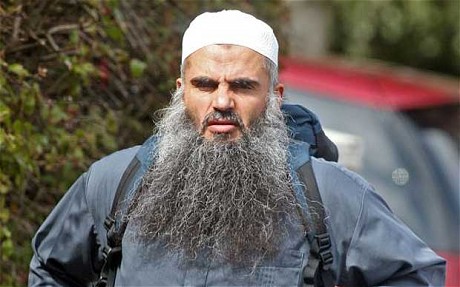

The deportation of a Jordanian Muslim cleric residing in the United Kingdom (UK) was prevented last week because of the possibility that evidence against him was obtained using torture. On 12 November, the British Special Immigration Appeals Commission decided that there was a “real risk” that Abu Qatada, whose real name is Omar Mahmoud Mohammed Othman, would be denied justice in Jordan. Despite the fact that he is wanted in Jordan for terror offences (the plotting of bomb attacks) and is, due to his links with al Qaeda, considered a security threat in the UK, he will not be extradited. This is a promising development from a legal perspective, since international law explicitly prevents the extradition of persons to third countries where there is a risk of torture. In this particular case, the concern is related to the right to a fair trial and specifically that evidence may be used which was obtained through torture. According to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), this continues to be a concern in Jordan.

The decision by the British Special Immigration Appeals Commission reinforces an earlier ruling of the ECHR, which stipulates that there was a risk that the fair trial rights of Abu Qatada would be violated (article 6 European Convention on Human Rights). In a similar vein, the British judges applied a three-step test to assess the risks Abu Qatada would face: Firstly, they looked at the possibility of a retrial on similar charges (in 1999 and in 2000, Abu Qatada was convicted in absence for conspiracy to cause explosions in Jordan). Secondly, they found there was a risk that statements made by key witnesses, which implicated the accused, were obtained by torture. Last but not least, the judges argued that there was a significant chance that those statements would be used as evidence against him. From a human rights perspective, the protection of fair trial standards for terrorism suspects, who run the risk of being unfairly tried in third countries, is a welcome one.

Nonetheless, the Abu Qatada case raises other human rights concerns in relation to holding potential terrorists accountable. The diplomatic assurances, which the British government had obtained from the Jordanian authorities to ensure Abu Qatada would not be tortured, were according to the ECHR “specific and comprehensive”. Yet human rights organisations including Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International and Justice question if diplomatic assurances against torture are ever sufficient. The main argument is that states under international law are obliged not to extradite a person to a place where there is a real risk of torture (Article 3 European Convention on Human Rights). They are concerned that, with this ruling, the ECHR has legitimised diplomatic assurance. Previously, Research Fellow Dr. Bibi van Ginkel, has argued that diplomatic assurance should only be used as a matter of last resort.

Furthermore, questions remain about the British Government’s intentions - did they applying anticipatory justice in their strategy to prevent terrorism? In the case of Abu Qatada, was he held accountable in anticipation of certain risks that have not (yet) materialised? To what extent is it justifiable to continue to try to hold the cleric accountable for his links with al Qaeda? Will he ever be able to prove his innocence or convince authorities that he has changed? For over ten years the British authorities have tried to extradite him for national security reasons. Between 2002 and 2005, he was detained without charge under anti-terrorism legislation, and from 2005 until last week he was kept in alien detention. The British Home Secretary stated “Qatada is a dangerous man, a suspected terrorist, who is accused of serious crimes in his home country of Jordan”, thereby perhaps implicitly suggesting that, whether a court convicts him on terrorism charges or not, he is a terrorist. This may indicate that in the fight against terrorism, the burden of proof has shifted from public authorities to potential suspects such as Abu Qatada. While in his case, there might be valid reason to believe he is a radicalised cleric with links to al Qaeda, from an anticipatory justice perspective, it raises the question as to what opportunities others in similar situations are given to prove that they do not support violent extremism or engage in terrorism? The British Special Immigration Appeals Commission’s decision in the case of Abu Qatada is therefore a step forward, concerning at least the rights to a fair trial for terrorism suspects.