On April 27 2018, a Europol press release announced that new action was underway to disrupt ISIS’[1] ability to spread its propaganda online. The press release referred to an operation that commenced two days earlier, which was led by the Belgian Federal Prosecutor’s Office and coordinated with six European countries (Belgium, Bulgaria, France, the Netherlands, Romania and the United Kingdom), as well as Canada and the United States.

According to Europol’s statement, the operation resulted in the seizure of servers by law enforcement, which would significantly curb the capacity of ISIS to spread its propaganda online and yield crucial leads to the servers’ administrators. Meanwhile, a new advanced referral process to take down domains hosting ISIS content was also announced.

The operation was said to target various prominent ISIS propaganda outlets: Amaq news agency, its al-Bayan radio, Halumu, and Nashir News.

The purpose of this piece is to examine the elements targeted by Europol’s operation in the context of ISIS’ global propaganda architecture, and to offer an external analysis on what the aim of the operation might have been. It is also observed that it is difficult to assess the efficiency of the Europol operation and what this operation demonstrates with regard to authorities’ broader fight against terrorist propaganda.

Telegram: the Source That Irrigates the Web

Briefly, let us recall how ISIS’ propaganda is structured online and how the dissemination of content is organised.

Since 2015, major web platforms have upgraded their monitoring of extremist content online. As a result, ISIS media activists have partially migrated underground, to places such as the deep web and encrypted messaging apps like Telegram, to spread their propaganda. In these environments they benefit from a certain ‘operational security’ that offsets the loss of immediate surface-web access, which is something they benefited from in the past.

Telegram’s channels are one of the functionalities that make it an app of choice for the jihadist group’s propaganda dissemination. Its channels send “push” content to subscribers and allow for one-way streams of communication where only designated administrators can post content, unlike groups where all members can typically share content. Additionally, channels do not publicly reveal information on the identity of subscribers, such as usernames.

Some channels on Telegram function as core propaganda channels, serving as a source for other channels. These core channels are only accessible to selected ‘verified’ individuals, who are often administrators (or members) of other channels (or groups) with larger pools of recipients. This is to avoid infiltration in order to make the core content arrive safely to the first circle of sympathisers, who will relay it to a wider audience. Some content also benefits from automatic relaying by bot channels. The spread of content across Telegram thus works in concentric circles, from core-channels to channels or groups with several hundred, if not thousands, of recipients or members.

It is predominantly from Telegram, the platform that irrigates the web when it comes to ISIS propaganda, that pro-ISIS media activists and sympathisers derive content and spread them to other platforms. In this process ISIS demonstrates its resilience and agility in a continuous ability to adapt the way in which it spreads its propaganda online.

ISIS Outside of Telegram

Alongside its activities on Telegram, ISIS also regularly pushes content directly to websites, social media, and file-sharing platforms. Links to the content published on these mediums are extensively shared on Telegram.

Some websites such as Halumu or Amaq (figure 1) constitute a ‘jihadi archive’ and contain a significant amount of videos, audio, and other publications. Certain websites also offer the ability to subscribe to a newsletter service, in order to receive the latest news updates via email, or a download link to a plugin that would automatically find the URL of the latest website following deletion of the previous one by authorities. The deletion of a website by authorities is a process that sometimes takes months to occur.  Figure 1 - Example of Amqq website serving as a 'jihadi archive' (June 2017)

Figure 1 - Example of Amqq website serving as a 'jihadi archive' (June 2017)

The Operation Targeted Websites That Were Accessible to the Public

Europol’s press statement gave few details on the operation’s scope, but two main elements have emerged: 1) the seizure of servers in the Netherlands, the US and Canada; and 2) measures to limit the abusive use by ISIS of top-level domain registrars.

Experts at Europol’s will most likely be well-aware of the propaganda architecture described earlier. However, the operation did not initially appear to prevent ISIS’ propaganda emanating from the source, namely proliferation via Telegram. Since April 25, the first day of the Europol operation, the flow of ISIS propaganda on Telegram remained quite steady, sustaining the usual fluctuations that cannot be attributed to exogenous factors.

Europol’s intervention on several servers and on the top-level domain registrars were likely aimed at achieving two objectives. Firstly, the targeting of websites directly accessible to the public, as for the most part Telegram remains ‘obscure’ to the general public; and secondly, the gathering of data that will potentially provide Western law enforcement agencies crucial leads in identifying ISIS’ sympathisers.

With regard to the operation’s claim to target the main ISIS websites, three portals were abruptly taken offline in near-simultaneous fashion: the war-news-agency (Amaq agency website), upload-files (a portal for hosting videos, statements, and claims), and the al-Bayan radio website. All of these websites have “.eu” suffixes and ceased to function upon the start of the operation. Websites such as these disappear regularly, but the coordinated timing does not appear to have been a coincidence.

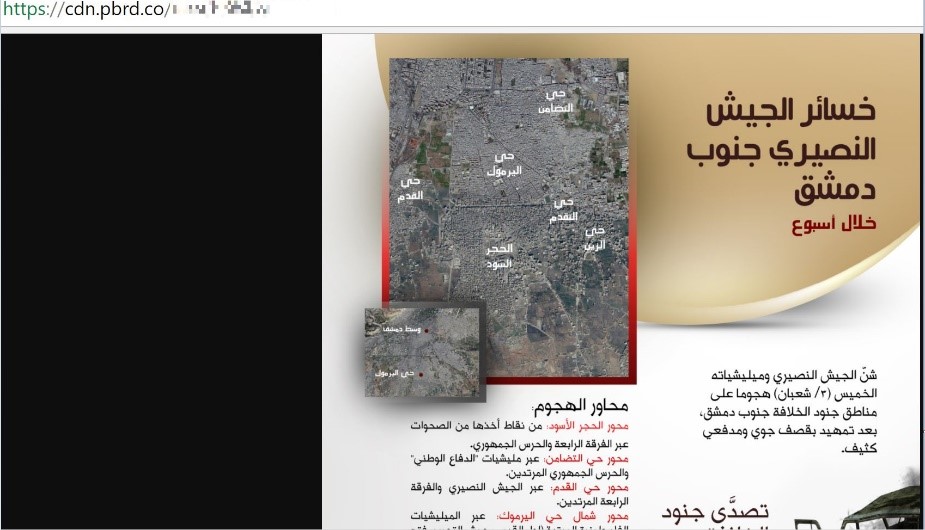

While some websites have indeed been compromised, the disruption remains minimal for ISIS propagandists. Content continues to surface on file-sharing platforms, and when necessary ISIS has been turning to obscure, little known platforms. An example of this is the use of image sharing portal pbrd.co, whose first instance of ISIS related material dates from the days following the operation (figure 2).

Figure 2 - pbrd.co link pointing to an infographic of weekly an-Naba 129 (20 April 2018)

Al-Bayan, a radio station operated by ISIS, used to broadcast on the FM frequency in Mosul during the ISIS occupation. More recently, it is operating online via a series of web domains with alternating suffixes such as .be, .pl, or .ua. It resurfaced on April 29, under a new domain that contained a .ru suffix, three days after Europol’s operation. The website offered a link to ISIS’ latest weekly newspaper, an-Naba 129, as well as a Firefox plugin for the Al-Bayan radio broadcast. On May 1st, the ISIS Amaq news agency website reappeared, with a .eu domain (figure 3).

Figure 3 - Amaq website with .eu suffix (1 May 2018)

In the aftermath of the crackdown, some questions are being asked related to intelligence gathering and ISIS’ ability to regroup online.

- How quickly can ISIS’ media activists compensate for the recent disruptions, acquire new servers and transfer massive archives of data, video and images?

- What evidence and intelligence can the seized servers yield? Among the possible options, law enforcement could identify IP addresses of computers that have been connected with those servers (to upload or download content), gather intelligence on the administrators of these servers and where they are located, or information on financial elements, and even web users who connected to the targeted websites. Some of this information might not be traceable or exploitable, which depends on the level of anonymity and operational security adopted by the administrators of these websites and their visitors. For instance, if visitors make use of VPNs to surf the web, less useful data could be collected. However, information that is collected in such cases could also yield valuable insights on the process or methodology used in administering servers and how the propaganda activities are conducted.

In summary, Europol’s operation does not truly compromise the flow of ISIS’ propaganda and should not be assessed solely by this benchmark, at least for now. Its effect could be felt if the seized elements yield enough exploitable intelligence on the sources of this propaganda, which can only be assessed in the middle term.

Additionally, effective curbing of propaganda from the surface web can only be achieved by a constant monitoring force that can implement swift removal or deletion of offending websites, servers and domains. Such a course of action is costly and is also associated with several complications. Legal, ethical and political questions arise about what type of content has to be removed, owing partly to the different views of countries on the boundaries of free speech. There are similar questions related to determine what kind of entity within a country would or should have the authority to make such assessments and decisions, if at all.

Content removal will be offset by fresh tactics from media activists, as has been the case in the past, where fragmentation of propaganda to various platforms could be observed and a growing use could be witnessed of obscure domain registrars, as well as hard-to-trace servers. These innovative tactics may result in prolonged deletion times that require similar anticipation and adaptability from the authorities. Moreover, a constant trade-off has to be made between swift content removal and the need to collect data over time. The latter could yield valuable intelligence, albeit at the risk of looking permissive from a political standpoint.

Europol’s operation discussed in this piece, besides confirming that international partners are working to tackle this together, indeed reflects that the fight against propaganda is inextricably linked to the crucial process of intelligence collection. It will hopefully enable actors like Europol to better address the challenge of targeting the online sources from which propaganda emanates, including those on Telegram, rather than trying to mechanically stamp out a seemingly infinite flow of terrorist content.

This Perspective originally appeared in a slightly different form, published in French with Ultima Ratio, IFRI’s Center for Security Studies’ blog, on May 3rd, 2018.

[1] Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, also known as IS, ISIL