Dabiq’s propaganda aimed at Western women is based on more than romance and sex, argues Kiriloi M. Ingram. A more nuanced understanding of IS’s appeal to women, in particular of the five categories of female archetypes into which IS tends to group women, would allow for more effective counter-strategies.

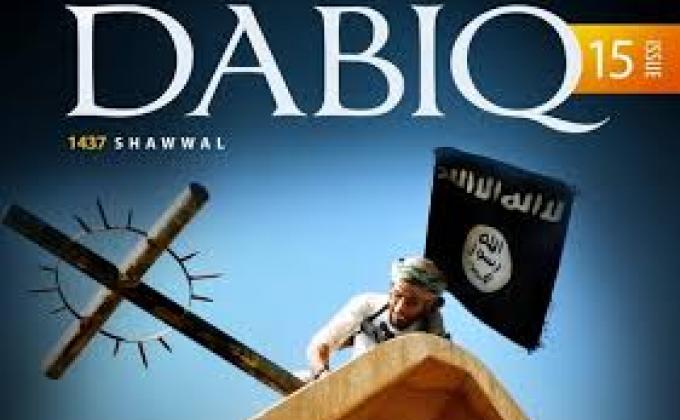

Recent setbacks in Syria and Iraq have not deterred the so-called “Islamic State” (IS) from using propaganda to appeal to Western women. Indeed, the latest issue of its English language magazine, Dabiq, featured two articles for female audiences. IS’s ability to attract Western women has captured the world’s attention, sparking fierce debate about their motivations. Unfortunately, this discourse has often become yet another forum for reproducing gendered stereotypes via sensationalised depictions of “jihadi brides” (or more derogatively “jihadi sluts”) falling for IS’s “eye candy” online.

There now seems to be a disproportionate focus on the idea that females join IS fuelled by sexual desire and romance: a product of analysis based largely on social media profiles. How security phenomena are understood shapes the strategies that are developed. In fact, a recent article argued that the flow of women joining IS could be stunted through sex education.

While romance and sex are important factors, it is crucial we adopt a more holistic approach to analysing the Western women of IS. For example, social media profiles are inevitably representations, personas of the people who own them. Thus, drawing on social media accounts alone to understand what is a complex psychosocial phenomenon is the equivalent of only using social media profiles to understand Western women.

There is much to be learned about what appeals IS believes will attract females by examining its propaganda. It follows that if IS saw romance as a key motivating factor, then Dabiq’s appeals to women would read like their own version of Bridget Jones’s Diary. It doesn’t.

So what does Dabiq have to say?

IS’s Five Female Archetypes

Based on analysis of fifteen issues of Dabiq, IS tends to portray women in five ways: contributor, mother/sister/wife, defender/fighter, corruptor and victim. Each of these female archetypes fits into one of two categories: part of the revered in-group identity and its divinely ordained solutions or part of a despised out-group identity and a cause of crises. Dabiq’s narratives thus compel their female readers to aspire towards the archetypes within the former but be wary of and reject those in the latter.

The most prominent archetype in Dabiq is that of “contributor”: the woman who performs hijrah to the Caliphate as an essential expression of her female Muslim identity. By fulfilling this obligation, these “contributors” not only actively solve their own individual crises and reverse the ills imposed on them by the West (a topic which is addressed in Dabiq 15’s “The Fitrah Of Mankind And the Near Extinction of the Western Woman”) but solve the Muslim community’s collective crisis through building an “Islamic-utopia.”

These narratives are strategically designed to frame women as having an important role in the Caliphate. After completing hijrah, women are promised a purposeful life with powerful roles as a “mother”, “sister” and “wife”. In contrast to “living amongst kufr and its people” with superficial relationships, women are promised a sense of belonging and unity in an everlasting sisterhood. As Mia Bloom asserts, promises of such relations can create anchors to ensure both men and women stay in the Caliphate.

The “defender”/“fighter” archetype is designed to further empower women via narratives that, for example, promote the fact that women receive basic firearms training or heralding the female San Bernadino shooter. However, Dabiq is quick to emphasise that a women’s jihad is “when you await the return of your husband patiently … when you teach his children the difference between truth and falsehood.” Nevertheless, women are still portrayed as the last line of the Caliphate’s defence – the final spiritual and physical defender of the home and family.

IS augments these positive archetypes with negative “corruptor” and “victim” archetypes. IS frames the “corruptor” archetype as female disbelievers and devious Muslim women who oppose IS’s prophetic methodology. On the other hand, Dabiq constructs the “victim” archetype as a product of IS’s enemies’ malevolence. This construct is also used to demonstrate how IS’s politico-military agenda can be the mechanism to save both Muslim “victims” and the corrupted. For example, an article justifying saby (enslavement through the war) written by an apparently female author frames IS as the champion, saviour and protector of both IS-aligned Sunni Muslims and the slaves:

"From the slave-girls are those that after saby turned into hard-working … seekers of knowledge after she found in Islam what she couldn’t find in kufr, despite the slogans of ‘freedom’ and ‘equality.’"

The latest issue of Dabiq devoted two articles to women, contrasting its typical single article in previous issues. Given IS’s recent losses in the Levant, this may be telling. Following the fall of Stalingrad, Nazi propaganda increased its targeting of women, calling on them to make greater sacrifices and encourage their husbands to engage in combat. It is plausible that IS may also increase its appeals to women as pressures mount. Expect inspiring stories and calls for “contributors”, “mothers”/“sisters” and “defenders”/“fighters” to perform hijrah and become bases of support for IS’s jihad or support terrorism in the West. Also look out for how the female archetypes are used to both positively and negatively motivate men.

Ultimately, if our understanding of what motivates women to join IS fixates on romance and sex, we cannot comprehensively understand the motivations of the “Caliphate’s women”. The more nuanced our understanding the more effective counter-strategies are likely to be. We can start by improving the field’s debate and remembering that counter-strategies are more likely to be effective if they seek to empower women rather than chastise and trivialise their value.

About the Author

Ms. Kiriloi M. Ingram is a researcher with the Australian National University’s Coral Bell School. Her research analyses how violent non-state political movements use propaganda to appeal to female supporters. This article is based on a conference paper delivered at the Women and Violent Extremism Conference (Canberra, Australia).